Some children don’t seem to like to read and some appear to really struggle to complete their homework. Most of the time parents think it’s just because they are lazy or want to play instead. But what if it’s not?

If your child dislikes reading and homework, it could be related to a vision problem.

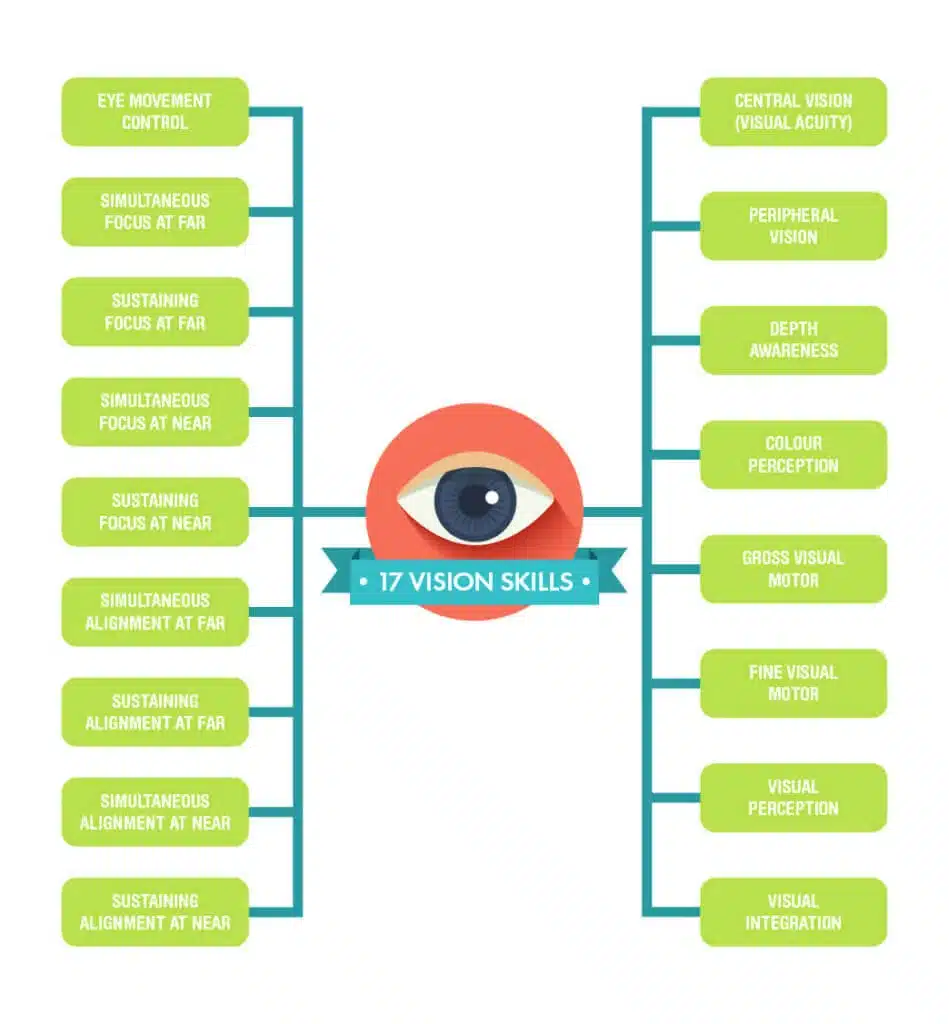

Most people think “good vision” only means being able to see the smallest line on a chart or recognising an object from a good distance or even having good eye health. But the truth is, seeing clearly is just one of about 17 different vision skills needed to have an efficient and accurate visual system.

This means that vision is more, so much more, than just seeing the small lines on the chart or in a book!

This means that vision is more, so much more, than just seeing the small lines on the chart or in a book!

Visual skills are developed over time, beginning from infancy and continues to develop as we grow. Some children, however, don’t develop these visual skills as well as others. Some children and adults lose them, for example, after a head injury, whiplash or concussion.

Behavioural optometrist Dr Soojin Nam comments, “When getting your child to do their homework is a struggle, when your child avoids or appears to dislike reading, they may just have an underlying vision problem.”

Behavioural optometrist Dr Soojin Nam comments, “When getting your child to do their homework is a struggle, when your child avoids or appears to dislike reading, they may just have an underlying vision problem.”

Vision problems can go undetected because the signs are not immediately obvious.

Signs and symptoms include:

|

|

Imagine yourself getting a headache after a few minutes of reading or having to take much longer to do 20 minutes of homework. Imagine not being able to remember what you’ve just read. Wouldn’t you hate reading too?

Lily was an 8-year-old who struggled with reading. As she read, she ended up seeing double. To compensate, her brain would have to work extra hard trying to visually analyse the words while comprehending the sentence. Her brain was overloaded and Lily was stressed. Understandably, Lily hated reading and refused to do her homework.

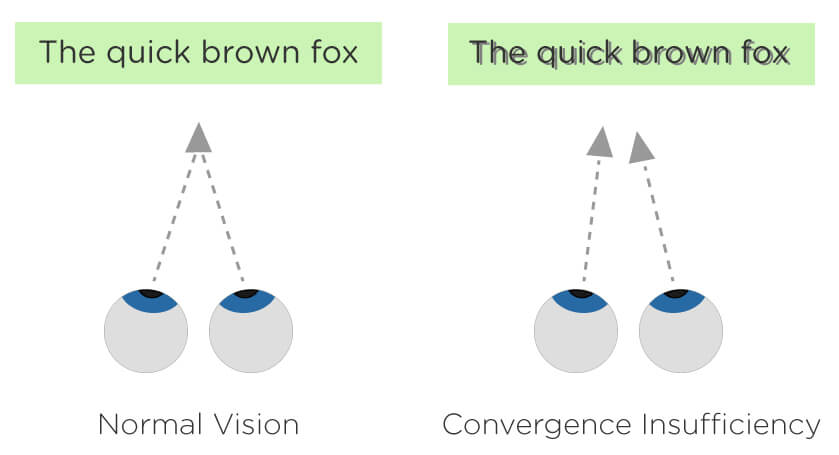

Convergence insufficiency is one of the most common visual disorders found in children struggling with reading. This affects binocularity, or the ability of the eyes to focus on an object to create a single three-dimensional image. To focus on a near object, your eyes converge and, hence, your eye muscles have to pull your eyes together. Its opposite is divergence, or when you let your eyes relax, or diverge, to focus in the distance.

Lily had convergence insufficiency, which means as she read, her eyes converged enough to focus on the words, but couldn’t sustain that convergence for long periods of time. Reading for Lily had been a very complex task done very inefficiently by a very distracted brain.

Optometric vision therapy is the solution for Lily. Vision therapy helped Lily’s brain improve its ability to coordinate the eyes as a team. The vision therapist trained Lily how to point her eyes at one place to make one image and then trained them to keep that single vision from one word to the next, again and again and again!

After vision therapy, Lily was a happier child, an eager learner and an honour student. Once her eyes were not uncomfortable when looking at close tasks for a long time, Lily discovered how much she actually enjoyed redaing.

Lily’s mum’s only complaint was: “I couldn’t get her to stop reading!”

Lily was just one of the 25% of school-age children affected to some degree by a learning-related visual condition and one in 80% of problem readers who lack visual skills.

Lily was just one of the 25% of school-age children affected to some degree by a learning-related visual condition and one in 80% of problem readers who lack visual skills.

Dr Soojin Nam (Optometrist) reminds parents, “Children are curious little things who love to learn, explore and generally get delight in new discoveries. When they avoid reading or learning, it may be due to a difficulty that relates back to a vision problem. Seeing clearly is only one aspect of vision. You also want to make sure that your eyes are comfortable when they are working and concentrating. This includes skills in focusing, eye teaming and tracking across a page. A comprehensive eye test with a paediatric optometrist can help uncover visual problems that can be corrected either with spectacles and/or vision therapy.”